Happy March, dear readers! In today’s post, I’d like to share with you my reflections on Meditations, private notes of the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius, dated to the last decade of his life, AD 170-180.

I love Meditations for so many reasons, but if I had to summarize all of these reasons into one sentence, it would be this: Meditations presents a worldview that meaningfully contextualizes the microcosm of the human being in the macrocosm of the world.

We find the worldview of an emperor heavily influenced by Epictetus,[1] a Stoic philosopher, and Heraclitus,[2] one of the Greek philosophers at the frontier of the foundation of Western philosophy.[3]

But more importantly, we encounter the Roman emperor in a dialogue with himself. In a memorable entry, Aurelius writes, “My soul, will you ever be good, simple, individual, bare, brighter than the body that covers you?” (MD 10:1).

In this post, I’d like to share with you three points from Meditations that made a particularly strong impression on me.

Harmony in chaos: Logos

Around 300 BC, when Zeno founded Stoicism, he made logos one of its fundamental terms. Logos[4] is a Greek term originally meaning word, and it refers to the animating energy that pervades the universe.

Before Aurelius, it had been used by Heraclitus, who defined it as an ordering principle of the Universe. (On a side note, Stoicism also uses the term to mean the faculty of reason in a human being.)

Referring to logos, Aurelius writes that it “informs all of existence and governs the Whole in appointed cycles through all eternity” (MD 5:32).

The way I interpret Aurelius’s words is that there is a universal law that governs individual human actions and helps maintain the entire creation. Aurelius uses the term logos to indicate this highest law or reason.

It can also imply that in aligning oneself with the universal law, it is possible to find harmony in the apparent chaos of this world.

Unity in diversity: Interdependence of life

Meditations presents a view that a human being is not a mere “cluster of atoms” as Epicureanism holds but that every being shares an aspect of divinity. Aurelius refers to the “fragment of himself which Zeus has given each person to guard and guide him” (MD 5:27).

He also acknowledges the shared divine source of the mind, writing, “a human being has close kinship with the whole human race – not a bond of blood or seed, but a community of mind. And [when you fret at any circumstance] you have forgotten this too, that every man’s mind is god and has flowed from that source” (MD 12:26).

Of course, recognizing this intellectually is one thing, but living this belief out in the give-and-take of everyday life is another thing.

But Aurelius’s words still give me hope because he believes in the mind’s freedom to choose. According to Aurelius, through being aware of and exercising one’s mind’s freedom to choose, a human being is enabled to work towards the attainment of virtuous qualities. He writes, “The directing mind is that which wakes itself, adapts itself, makes itself of whatever nature it wishes, and makes all that happens to it appear in the way it wants” (MD 6:8).

Eternity in time: Life and death

Cassius Dio, a senator and historian who is one of the major sources of Roman history during Aurelius’s reign, wrote, “[Aurelius] did not have the good fortune that he deserved, for he was not physically strong, and for almost his whole reign was involved in a series of troubles. But I, for my part, admired him all the more for this very reason, that amid unusual and extraordinary difficulties, he both survived himself and preserved the empire.”[5]

During his reign of the Roman empire for almost two decades, Aurelius faced constant invasion and fighting on the frontier[6], a revolt by his general Avidius Cassius, and the deaths of his co-emperor, wife and children.

Despite or perhaps because of the adversities in his life, Aurelius maintained a deep awareness of the transience of the world. One of his entries reads, “All things are in a process of change. You yourself are subject to constant alteration and gradual decay. So too is the whole universe” (MD 9:19).

Within the context of death, an essential question about life arises: How should a person live?

In Meditations, Aurelius answers this question: a person’s endeavours should be directed toward “a right mind, action for the common good, speech incapable of lies, a disposition to welcome all that happens as necessary, intelligible, flowing from an equally intelligible spring of origin” (MD 4:33).

Through identifying a human being with aspects beyond the physical body, the Meditations views mortality as a motivation for leading a meaningful life. In Meditations, Aurelius reminds himself to think of death as an event as natural as “corn being reaped” (MD 11:34).

Aurelius regards death not as the extinguishment of life but rather a catalyst for its continuous renewal.

And for all his reflections on how he will soon be gone and forgotten, Aurelius, nearly 2000 years since his Meditations was written, is now widely known to us as a Stoic philosopher.

Aurelius’s writings stand as a powerful testament to one person’s efforts to understand the physical and spiritual dimensions of the human being. More importantly, it presents an example of a person who has fought the battle of self-mastery in the midst of extraordinary circumstances.

And life perhaps could present no greater challenge to a human being than that of attaining self-mastery.

Thank you for reading! Please feel free to comment or share this post if you feel like it. I’m open to discussing any of these points further.

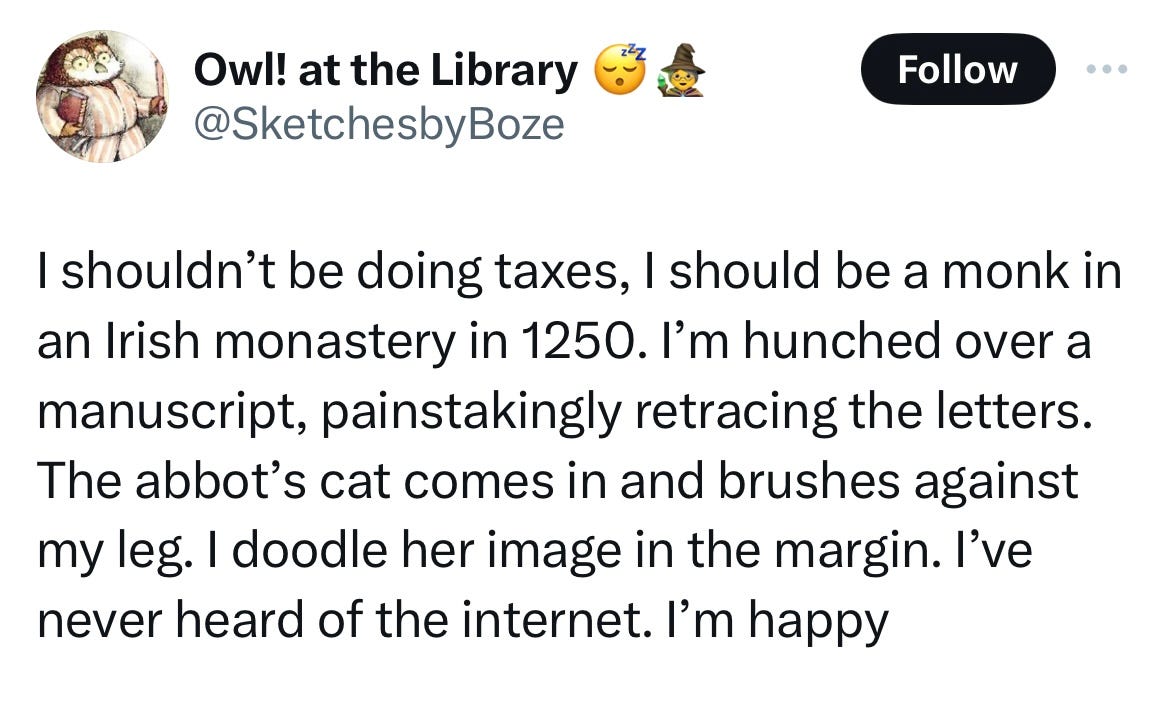

PS: One more thing! I recently came across the below tweet that speaks to the core of my being. I know, I know I am so dramatic, and I say this about so many things, but honestly, this tweet resonates with me so deeply.

[1]. Marcus Aurelius, Meditations, trans. Martin Hammond (London: Penguin Books, 2006), 4.

[2]. A.R. Birley, Marcus Aurelius: A Biography, rev. ed. (19; repr., New Haven, CT. : Routledge, 2000), 217.

[3]. Anthony Kenny, A New History of Western Philosophy in Four Parts (Oxford, England: Clarendon Press, 2010), 19.

[4]. Encyclopaedia Britannica Online, s.v., “Logos,” last modified May 21, 2012. https://www.britannica.com/topic/logos.

[5]. Cassius Dio Cocceianus, Dio Cassius: Roman History, trans. Herbert Baldwin Foster and Earnest Cary (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press 1914), 36.

[6]. Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 155.